The roads told the story of what lay ahead in the prairies with most communities often separated by fifty to a hundred miles. Stagecoach roads held hard-punched strips of dirt between center humps. During dry season, dusty roads would like to choke a man who passed. In the wet, muddy roads could near bury a man and any wheeled conveyance, spare not the poor horse or ox stuck in the road, holding more value than the cargo it pulled.

In the clay belts, roads threw sand and wet grit upward, stinging the bellies of fast horses, and giving a dangerous slip to near every hoof fall. At river crossings, men with rifles insisted on road tolls. When roadhouses offered pallets and a meal, you were likely as not to get thin stews and lousy blankets for the night.

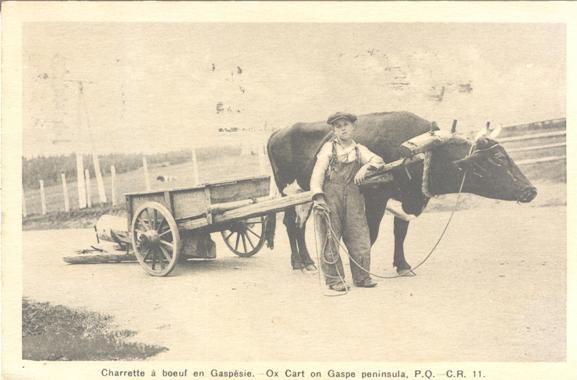

Gone were shallow Quebec carts found throughout the Maritimes, Quebec and Ontario with solid bodies on four sides and a tail bone that could rise or fall.

Courtesy of https://goo.gl/images/jzYxHC

In the prairies Red River or Métis carts moved men and harvests from Winnipeg to the Rockies with their deeper bodies and four open sides.

Odd spaces between rows of cabins and shanties became new, unplanned roads. Bunk houses and shacks with tar paper roofs announced roadways into larger towns where tent cities butted against proper wooden or brick buildings with alleys that accumulated evaporated milk cans and crushed tins of Copenhagen snuff.

Wagon paths sprang up where oxen pulled crops to the nearest grain elevator. The more traffic the wagon paths bore, the faster deep ruts turned into hard-packed wagon roads.

Wagon paths thinned to animal trails where no men farmed or ranched. Once those played out, then feet touched open range with no discernible boundaries. The road shifted to deep potholes and masked wallows quick to turn an ankle where wild scrub and prairie grasses hid snakes and critters of all kinds.

Families lived through hard times with the womenfolk and children in a tent on some unnamed road, their men in some camp with no pay left for store-bought food and no way to grow any. Entire families might live on the side of a road: father dead, mother ill, two or three children crying with outstretched hands and thin arms trying to buy water from any passerby.

Large farms ran work camps for seasonal pickers with good wages at $1.75 a day, and weekly board of $4.60. Advertisements asked for ten thousand pickers but only took six, their intentions clearly defined. Hungry men walked long and hard on roads. Camps paid wages once a month where a foremen might not report a man’s death for a stretch, pocketing his earnings. One camp foreman disappeared with the monthly payroll, never to be seen again on any road. After the wet season started, there would be neither work nor pay.

Groups of farm pickers, ten to twenty, might watch you pass on the road, follow you to your camp and settle themselves nearby. Come chow, they might walk in one by one, humble-like, and try to buy a meal.

Follow a road by railroad tracks and ash could blacken your clothes or cinders from wood-burning engines scorch hat or hair. Sleep near tracks and the squeals of iron wheels would turn ears numb with persistent throbs.

Some sights roiled men’s blood, like leaving a starving family by the side of the road, or finding a slavered mare unbridled with bruises on her underbelly and no owner in sight. Many of God’s creatures traveled the prairie roads, but no one could save them all.